Shellburne Thuber recalls the first day she entered her therapist’s room. It was located in an old brownstone and offered a view over a street lined with cherry blossoms. It was also high above the street. Thurber said to Jess T. Dugan, a fellow photographer in an interview that appears in her new book analysis(Kehrer Verlag), she felt like she was in the treehouse.

The brownstone office was not one of the interiors in Analyses, a collection of photos taken in the offices of psychoanalysts in 1999 and 2000. But Thurber worked with her therapist at the time she began the project. Her experiences are reflected in her work. It began in Buenos Aires, with Gela Rosenthal as an analyst, who allowed Thurber to photograph her office before introducing her to other analysts in the region.

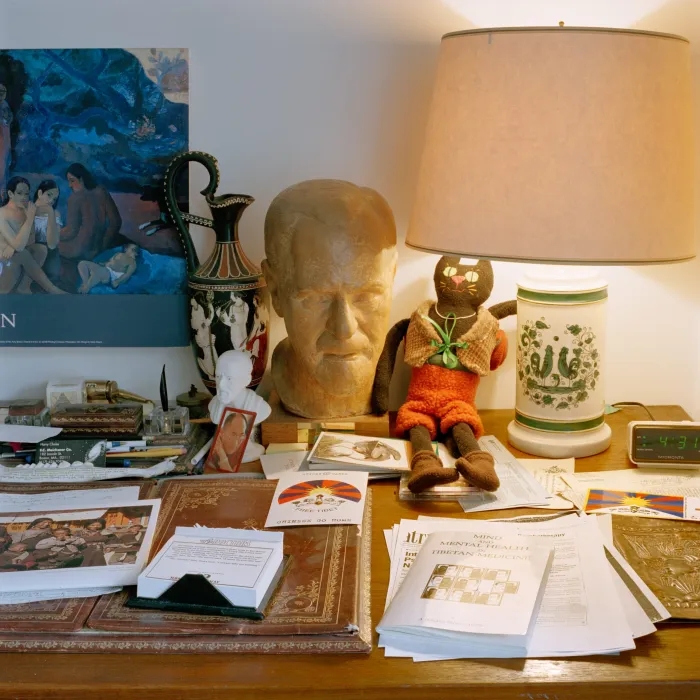

Thurber photographed the offices of analysts in the Boston region, but always without people. But somehow their memories and histories were imbued into the images. She took her time to absorb the space, focusing on important details.

The book begins with a note by Lia Gangitano that notes how many times Freud’s photographs and artworks appear, as well as boxes of tissues.

The question of belonging is always present: Do these rooms belong to an analyst, who has carefully designed and curated this space, or do they belong to a patient, who projects his/her own experiences on that space?

These offices are often located at the homes of analysts. They’re also very personal to patients. Daniel Jacobs is a Boston Psychoanalytic Society Training and Supervising analyst. In an essay written for the book he writes about how he’s interested in the reactions of patients to his office. One patient may find that the analysts’ chairs are too close to them, while another might think they’re not close enough.

Thurber’s work is characterized by this ambiguity of public and private space. It invites us as readers to adopt these spaces as our own. We can project without knowing anything about the visitors or owners of these rooms. You might see glimpses of yourself or your fantasies if you look closely.

Thurber took these photos more than 20 years ago but they still feel timeless. Thurber tells Dugan that she chose to photograph the spaces in color because, unlike Edmund Engelman’s famous photographs of Dr. Sigmund’s couch in his famous picture, Thurber wanted to make these offices feel like they were in today’s world. They feel “lived-in” even now.

The offices of these psychoanalysts are not empty, even though there is no one in the photos. Analyse focuses on the conscious and unconscious mind of the individual, but also the connections that we make. Thurber is still friends with many of the analysts who are featured in the book. She tells Dugan that her therapist is no longer with us, but the work she did with him continues to guide her through life. She dedicates her book to him.